Panama is often perceived as a transit hub—a place we pass through rather than stay. A stopover, not a destination. It lacks, many think, the glamorous eco-tourism reputation of its neighbor, Costa Rica. Yet this view is incomplete, and ultimately unfair.

I have to admit that I shared this misconception myself until recently. It was only while preparing my trip that I began to grasp how much Panama has to offer, how multifaceted this small Central American country truly is. I would like to invite you on a brief journey through time and terrain—the same one that dismantled my own prejudices.

This trip was wrapped into another, more intimate experience: traveling alone with my eight-year-old son, Max.

I try to take one-on-one journeys with each of my children whenever I can. They create a rare kind of closeness—time that belongs only to us, while allowing each child to feel singular, seen, and initiated into the beauty of this planet.

A Bridge Between North and South America

Many millions of years ago, Panama was an archipelago of volcanic islands, shaped by restless tectonic forces. Gradually, a narrow land bridge emerged, joining two continents and separating the Pacific from the Atlantic.

Then, around three million years ago, when Panama finally rose, continents leaned toward one another: cats, bears, and horses drifted south, while armadillos endured and great ground sloths—the size of elephants—lumbered north, slowly, toward a future that would not keep them. In crossing that slender strip of land, life itself was rearranged, with consequences still breathing—or absent—today.

The waters, too, went their separate ways. The Caribbean Sea grew warmer and saltier, lush with corals, while the Pacific became colder and less lucid, edged by mangroves and shaped by upwelling currents.

At the Biomuseo in Panama City, these distant times feel briefly within reach—as if memory itself were built into the walls.

The Indigenous Way of Life

The day that stayed with me most was the one spent with the Emberá. Their way of living comes closest, I imagine, to what life in Panama might have felt like when great ground sloths still roamed these lands.

When we arrived with the other visitors at Emberá territory, we first stepped into a canoe to navigate the Chagres River. Emberá men were waiting for us, wearing their traditional attire—minimal garments, skin marked with jagua body paint, beadwork around necks and wrists.

They guided us along a river embraced by rainforest on both sides, a river that for thousands of years has sustained them with fish. Warm wind brushed my face, and joy rose in me. The canoe ride felt like stepping into an old adventure film, where jungle and water still held the upper hand.

We then turned into a smaller stream that led us to an inviting waterfall—not too small, not too overwhelming. Swimming beneath its cascade became the greatest highlight of the whole trip for my son. When it was time to leave, it took real effort to pull him out of the water.

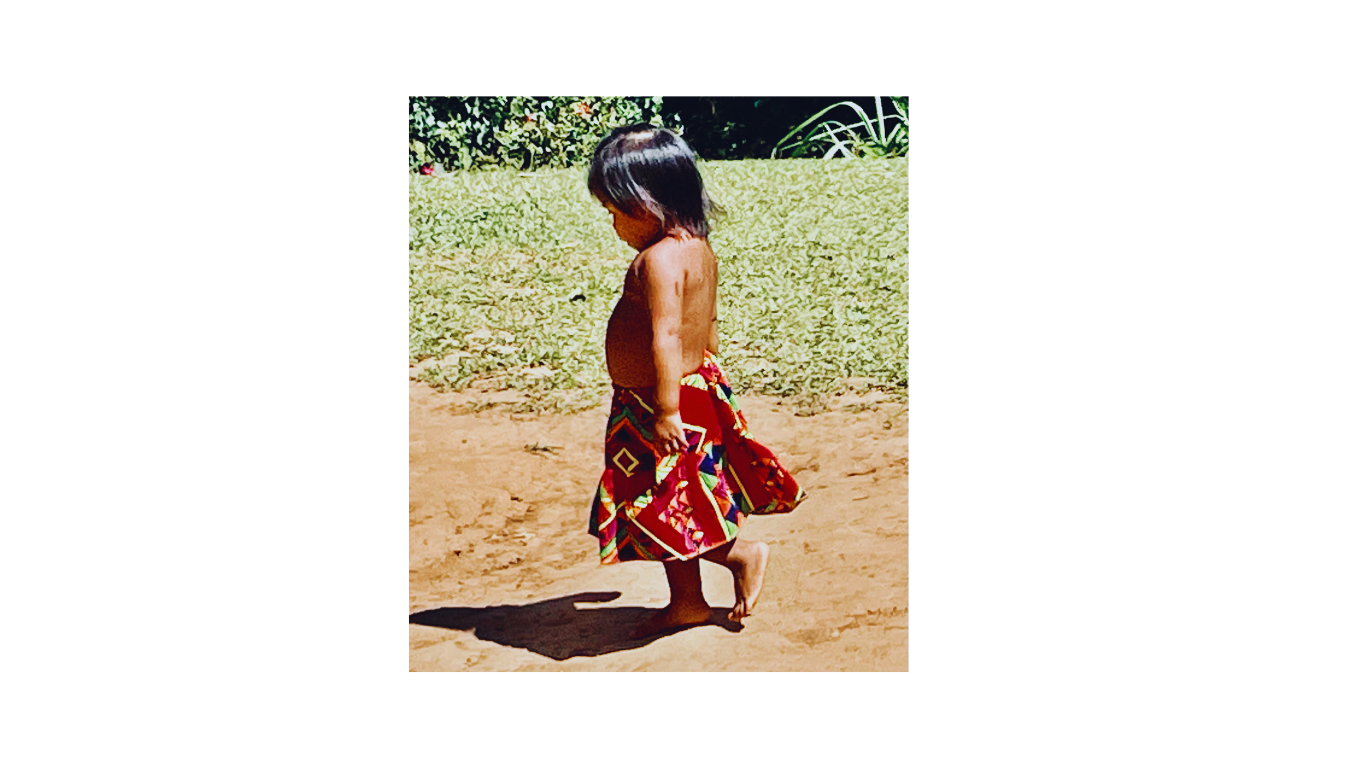

From there, the canoe brought us to an Emberá village. Women of all ages, dressed in colorful traditional clothing, hair crowned with red flowers, greeted us with handshakes, lined up on the stairs.

I kept wondering whether they always dressed this way or whether these clothes were worn mainly for visitors. The occasional small canoes passing by—with families dressed like other rural Panamanians—answered that question: tradition here is chosen, and culture adapts.

Lunch was prepared by Emberá women—tilapia, fried bananas, and fruit for dessert—served with such beauty and care that many businesses could learn from their sense of simplicity and ecological grace.

While we ate, they explained how they make their handicrafts.

What we experienced felt like a well-shaped meeting point: immersive for visitors, and for the Emberá a chosen economic path—a way of keeping traditions alive on their own terms. The way local and visitor intentions met felt neither artificial nor forced, but thoughtful, educational, and deeply worth experiencing.

Where Traditional and Modern Worlds Meet

Before lunch, we toured the village. We learned how their houses are built on pillars so they can live in rhythm with the river’s changing moods. Some straw roofs now carry solar panels, allowing access to electricity otherwise absent in the area.

They built their own school first; later, the authorities provided a Spanish-speaking teacher. Today, young people speak both the Emberá language and Spanish, giving them more possibilities beyond the village.

According to our guide, many young people dream of leaving for the city. But even with good Spanish, they often lack the skills and connections needed to fit into urban life. Life in the city is expensive, and without stable jobs, many return—drawn back to their traditional way of living.

Although the two worlds meet every day, some rules remain firm. Outsiders cannot live in Emberá villages. And Emberá who marry outside their community must also live beyond the village borders.

Tradition here is not a costume, nor a museum piece. It is something lived, adapted, protected—and negotiated with the present.

Old Panama and Casco Viejo

The Indigenous way of life was profoundly disrupted when Spanish colonizers arrived. The ruins of Old Panama bear witness to that moment—now carefully shaped for curious minds who want to understand how the first Spanish settlers once lived.

Casco Viejo, only a few miles away, became the new center after pirates destroyed the old city in 1671. It was easier to defend, and so history moved there. With its colonial architecture, some houses today look freshly restored—colorful, proud, luminous—while others stand pale and weary, whitewashed and tired.

This mixture reminded me of Cartagena, but also of Tallinn in the 1990s, when renovated buildings stood beside those still marked by the Soviet years.

The colors of Casco Viejo are not only in the buildings, but in the people too. Bright yellows, purples, mint greens, reds, oranges—Panama dresses itself in color.

But contrast goes far beyond Casco Viejo. All of Panama City feels like a mosaic: dense clusters of gleaming skyscrapers standing beside marginalized neighborhoods, parallel worlds coexisting, touching, yet rarely meeting.

The Canal

The country is primarily known for the Panama Canal, completed in 1914. Its role as a center of global trade has shaped Panama into one of the most economically dynamic countries in Central America.

What is less often remembered is the human cost. More than 22,000 people died from yellow fever and malaria during the failed French attempt in the 1880s. When the French withdrew, Roosevelt saw opportunity, and Americans soon took over construction. Since 1999, the canal has been fully Panamanian.

At Miraflores Locks, you can watch immense ships rise and descend within minutes, adjusted carefully to the canal’s shifting levels—engineering performing its daily miracle.

Nearby, yellow taxis linger like remnants of another era: older cars, older drivers, higher prices. Uber, by contrast, offers newer cars, younger drivers, and cheaper rides. Yet when my phone lost signal near the locks, I was “forced” into a taxi. The driver navigated not by street numbers or location pins, but by memory—what stands beside your hotel, what used to be there—nostalgic of a time when the canal itself was still held by others.

Oro de Panamá es Verde

The gold of Panama is green. The country holds exceptional biodiversity. Because the rainforest is dense and mosquitoes relentless, much of it is shown to visitors by boat. On Gatun Lake, small boats carry “monkey whisperers” whose work is sound—to call monkeys from hidden branches toward the water. Some species live only here, nowhere else on Earth. We met three different types of monkeys, each with its own way of moving, behaving, and living, and saw an iguana perfectly matched to its background. My son’s favorite by far were the capuchin monkeys, with their white faces.

Even nature, it seems, is partly revealed through movement.

Darién Gap

Much less known is that in the 2010s and early 2020s, the Darién Gap became one of the most important—and dangerous—migration corridors in the Americas. It is the only land route between South and Central America, and hundreds of thousands of people—especially from Venezuela, Haiti, and other countries—have crossed it on foot.

They face dense jungle, flooding rivers, crime, and total lack of infrastructure. Dehydration, venomous animals, robbery, kidnapping, sexual violence, disease—and sometimes death. In 2023 alone, more than half a million people made this crossing.

Just as Panama once carried ancient animal migrations that reshaped biodiversity, today its jungles serve as a modern crossroads for humans—not in ease, but in hardship and hope. Where once sloths and saber-toothed cats walked in geological time, now people walk in fear and faith, carrying children, memories, and the stubborn belief that somewhere ahead, life might open again.

Leave A Comment