I once told you about the embodied sensation of becoming a battlefield. Cancer claiming new ground, one cell at a time.

But I have since learned that was only half the story.

Other wars unfold within — unseen, unmeasured, yet no less fierce.

Man’s Search for Meaning

This diagnosis, strange as it may sound, has been a blessing.

Among the many things that arrived with it — fear, surrender, uncertainty — came an unexpected companion: meaning-centred psychotherapy. From the first session, I knew we belonged together.

The approach is rooted in Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, the work of a man who turned his experience in concentration camps into a new way of thinking in psychotherapy.

His teachings resonate with me: that life demands meaning; that meaning itself is the deepest engine of our behaviour; that even when pain is unavoidable, our attitude remains a choice.

Frankl wrote:

“We must never forget that we may also find meaning in life

even when confronted with a hopeless situation,

when facing a fate that cannot be changed.

For what then matters is to bear witness to the uniquely human potential at its best,

which is to transform a personal tragedy into a triumph,

to turn one’s predicament into a human achievement.

When we are no longer able to change a situation,

just think of an incurable disease such as inoperable cancer,

we are challenged to change ourselves.”

How could I transform my cancer journey into something useful and good? How will I change?

Woman’s Search for Meaning

I was asked to reflect on who I was before the diagnosis, and who I am now.

These days, I feel mostly like a woman in midlife, a mother, a wife, someone still learning to belong in her own skin.

Someone who cherishes experiences over things, and finds meaning in helping others, caring for our planet and mending what can be mended in myself.

Someone easily carried away by new ideas, by the impulse to reimagine and improve what already exists.

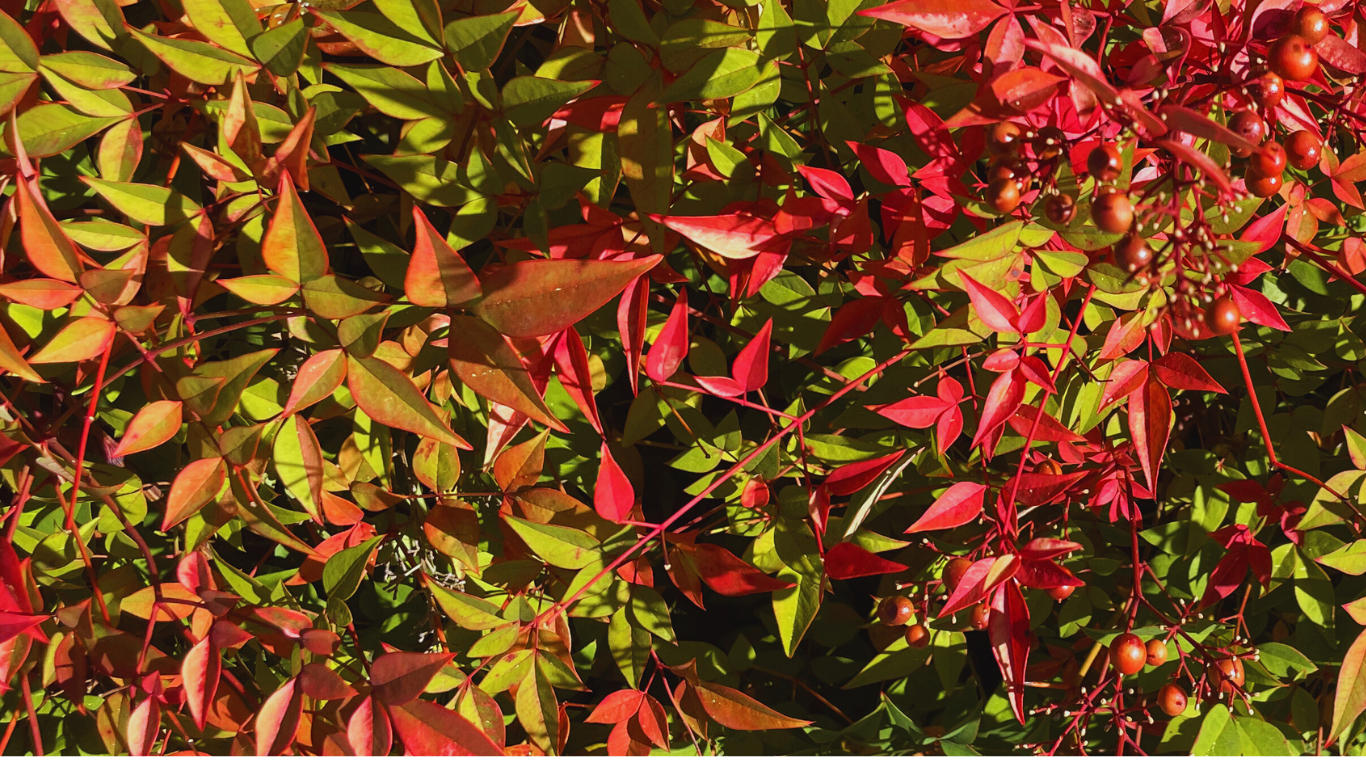

A being enchanted by nature, by travel, by the alchemy of words – the way they make sense of both the ache and the wonder.

New Balance of Powers

They asked how cancer has shaped my identity — what now feels most meaningful to me.

It seems I have been gifted with gentler eyes. I look at my family and see us differently. Where I once saw too much — children too loud, too restless, daily life simmering with small conflicts — I now see a single living organism: messy, yes, but united in its own imperfect rhythm, trying each day to do its best.

Before the diagnosis, I often felt trapped in an overdose of caretaking — the scaffolding that keeps a large family upright. My mind insisted that I could never balance the duties of motherhood with my longing to bring my green startup to life.

Now, being a mother — with all its mundane, repetitive tasks — feels less like an obstacle and more like a calling.

I used to be addicted to movement, to the idea that life’s fullness could be measured in countries crossed. But I have learned that if time ever became short, I would rather curl up beside my daughter, breathing in the scent of her hair before she falls asleep.

And as for writing — it has begun to overflow all boundaries, like spring water finding its way through stone. It moves through every part of me now, unstoppable, alive.

The ‘burning’ battle I cannot escape

These days, one struggle overshadows all others in the shifting landscape of who I am becoming:

What kind of woman do I want to be?

Some of us — we live with possibilities our grandmothers never had.

Do I want to be the woman who refuses to let cancer dictate her fate —

who removes every place it could hide and feed?

The one with new, symmetrical breasts that will barely age,

that might still stand proud in a nursing home —

if I make it that far.

The doctors call it the safest path, the way to peace of mind — to rebuild what was taken, to leave nothing for fear to claim.

And yet, I wonder — would that be strength, or fear disguised as control?

Would I be protecting my body, or merely guarding my certainty?

Or could I become the woman who chooses to go flat —

to redefine femininity beyond her breasts,

to stand as a visible witness to what cancer takes.

Perhaps my story will be written on my chest in a gentler way:

one breast given at birth,

the other shaped from the tissue I earned through motherhood —

recycled, redeemed.

As fate would have it, one of these women I am called to become.

Some of us — we carry our stories woven through our breasts.

Loved this paragraph ❤️

“I used to be addicted to movement, to the idea that life’s fullness could be measured in countries crossed. But I have learned that if time ever became short, I would rather curl up beside my daughter, breathing in the scent of her hair before she falls asleep.”

Thank you Jim!

Dear Veronika, I also love the paragraph Jim loves. The best place to be, is being curled up beside our children 😉

Thanks Sara!

One of my friends chose to wear a prosthesis bra. As her sister had same surgery, she didn’t doubt about her choice and it seems she had never regretted it. Indeed, attitude means a lot. I’ve been questioning myself since then what would be my attitude.

Thank you, Maral, for sharing your reflection. I will look into the prothesis bra options here as well. Sending you and your family much love!

Dear Veronika, I’ve been reading your posts since you started reflecting on this latest difficult, but also luminous personal journey before and after your surgery and thank you for them. Yes, thank you for being so honest, so deep in sharing what you have been through with your own, unique voice and feelings. It was also wonderful to read about your recent trip to Panama with your son; so much life, such incredible colors! I wish you well, and think of you even if I don’t write. A big hug from afar.

Dear Gloria, Thank you so much for your kind message—it truly touched me. Knowing that my words have reached you in that way means more than I can say. I have been thinking of you too, and I send you warm greetings from California.